|

Measure 11 - The Rest of the Story CRIME VICTIMS UNITED |

On June 15, 2003, The Oregonian ran an article on Measure 11 and its impact on the Oregon criminal justice system. The article contained some inaccuracies and several omissions which added up to a faulty portrayal of what Measure 11 has meant for Oregon.

In the following rebuttal, material from the original article is presented in italics, with Crime Victims United's response following.

1. The Oregon Legislature had lengthened sentences for rapists, murderers and other violent criminals . . .

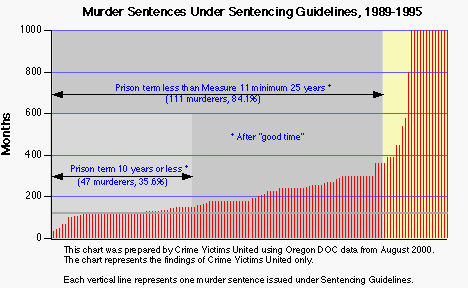

When the legislature adopted Sentencing Guidelines in 1989, Crime Victims United founders Bob and Dee Dee Kouns warned the legislators that the minimum sentences were out-of-line with the values of the people of Oregon and would not stand. The best illustration of this is the 10-year minimum sentence for Murder which, after earned time, meant eight years in prison.

Crime Victims United has examined each of the 132 murder convictions sentenced under Sentencing Guidelines which took effect in November of 1989 and was superceded by Measure 11 in April of 1995. 47 of the 132 murderers, 35.6 percent, received sentences which, after earned time, come to 10 years or less. The median prison term for a murderer was 12.5 years. These figures are for Murder convictions, not Aggravated Murder which is not covered by Measure 11.

One of the 66 murderers in the lower half of the distribution is James Daniel Nelson. As reported in the 6/17/2003 Portland Tribune, Nelson served less than eleven years for the 1992 murder of a 15-year-old boy. He is now the suspected ringleader in the recent assault, stabbing and burning murder of Jessica Kate Williams in Portland. This murder occurred less than three months after Nelson was released from prison. Had Measure 11 been in effect in 1992, Nelson's sentence for the first murder would have run through the year 2017. This is one of many such cases.

2. Opponents warned that Measure 11 would force the state to spend hundreds of millions of dollars building and operating the prisons needed to hold the flood of inmates serving longer sentences. Voters still overwhelmingly approved the initiative in 1994. And nearly nine years later, both supporters and opponents of Measure 11 can say they were right.

In fact, opponents were way off the mark. The financial impact statement said that Measure 11 would require 6085 additional prison beds by 2001. This estimate was very prominently featured in the voters' pamphlet arguments in opposition to Measure 11.

The actual impact in terms of prison beds as of July, 2001, according to the Oregon Department of Administrative Services (DAS), was 2519. (This number consists of 1638 beds for Measure 11 prisoners and 881 beds for non-Measure 11 prisoners who DAS claims got longer sentences because of Measure 11.)

So opponents overestimated the financial impact of Measure 11 by a factor of 2.4. This can hardly be characterized as being "right".

3. Violent criminals serve two to three times longer . . .

Measure 11 sets minimum sentences that are two to three times the sentencing guidelines minimums. Measure 11 does not require a two to three times increase in sentences across the board.

4. But like other big policy choices from a decade ago -- creating a model health plan and sharply reducing property taxes -- punishing criminals more harshly has led to unforeseen consequences as Oregon grapples with its worst fiscal crisis in a generation.

The only things unforeseen about Measure 11 is that the drop in crime has been far greater than expected and the cost has been far less than predicted. As we will substantiate below, Oregon's violent crime rate dropped 41 percent from 1995 to 2001 while the number of extra prison beds required by Measure 11 was less than half the original estimate.

We do not claim that Measure 11 accounts for the entire decrease in the violent crime rate but we do believe that it made a substantial contribution.

5. In order to keep violent criminals locked up, lawmakers have slashed money from the part of the criminal justice system . . .

Not surprisingly, legislators have made protecting people from violent criminals and serious sex offenders a top priority. They have the discretion to prioritize property crime and community corrections any way they want in relation to all government expenditures, not just in relation to Measure 11 expenditures.

6. And as the local system focused its shrinking resources on the dangerous criminals getting out of prison on parole, it increasingly ignored more than 18,000 mostly property and drug felons sentenced to probation and allowed to remain in communities and neighborhoods across Oregon.

If the budget really is a zero-sum game between Measure 11 and parole and probation, as the article repeatedly represents, then the alternative to allowing property and drug felons to remain in the community is to allow violent criminals and serious sex offenders to remain there. What sense does that make?

7. And Patridge points out that spending on corrections is still relatively small -- less than 10 percent of the state's budget.

One of the major misconceptions that people have is that prisons devours the majority of our budget. This is far from the case. After all of the budget cuts, the corrections budget for 2001-2003 was 7 percent of the total discretionary budget. Measure 11 accounted for about 1.4 percent of the total discretionary budget, and this is for arguably the most important duty of government.

Measure 11 cost was calculated as follows:

Average Measure 11 impact for biennium: 2,897 (from DAS)

"Impact" is the number of prison beds directly or indirectly required by Measure 11.

Total cost: 2,897 * $27,000/year = $78.2 million/year = $156.4 million/biennium

The $27,000 figure is the Oregon Department of Corrections' $23,000 per prisoner, per year figure plus $4,000 per year for debt service for prison construction.

From July 1, 2001 through June 30, 2002, while Measure 11 cost taxpayers $73 million, the Public Employee Retirement System cost them more than one billion dollars. (Source: PERS 2002 Annual Report, page 64.

8. Kulongoski said Measure 11 probably casts too wide a net . . .

The article fails to mention a point that is very important to understanding Measure 11.

Since the voters approved Measure 11 by a two-thirds majority in 1994, exceptions have been created by the legislature so that now, under some specific circumstances, judges can exempt offenders from Measure 11 sentencing for Sex Abuse in the First Degree and for all second-degree crimes except Manslaughter in the Second Degree. Furthermore, it is widely acknowledged that prosecutors use their discretion to further narrow the net.

9. The Legislature responded in 1989, setting uniform prison terms based on the crime's severity and an individual's criminal history. Inmates had to serve at least 80 percent of their sentences. The guidelines lengthened the prison terms for violent crimes. The average sentence served for rape or sodomy increased from about three years in 1986 to more than six in 1994, according to a study by the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission, a state agency. Time served for homicide tripled, from three years to 10.

Measure 11 was not about average sentences. Averages are notoriously misleading. Among the 132 murderers sentenced under Sentencing Guidelines is one who received a sentence of 1085 years. This one sentence completely skews the average.

Measure 11 was and is about minimum sentences because that is where Sentencing Guidelines was way out of line with the values of Oregonians.

10. Some states had made long sentences mandatory after a third serious conviction -- the "three strikes" laws passed in California, Washington and elsewhere. Mannix's proposal was a one-strike law.

This is a bogus argument straight out of the playbook of the Measure 11 opponents who used this slogan to confuse the voters during the Measure 94 campaign.

Measure 11 covers violent crimes and serious sex offenses only. California's three-strikes law covers less serious crimes such as burglary, attempted robbery and some forms of drug dealing, and any felony, such as auto theft or shoplifting, can constitute the third strike. Furthermore, "out" is widely interpreted as "life in prison". The longest Measure 11 sentences is 10 years, except for the 25-year sentence for murder.

11. After Measure 11 passed, lawmakers expanded the number of crimes it covered, creating separate mandatory minimum sentences for chronic property criminals, drunken drivers and sex offenders.

Measure 11 does not and never has covered any type of property crime! Nor does it cover drunken driving. Legislators have increased penalties for repeat offenders of those crimes but this has nothing to do with Measure 11. These other laws could be repealed without affecting Measure 11 in any way.

12. From 1994 to 2002, the state went from 47th to 10th nationally in prison growth, creating 5,200 prison beds and paying counties to jail more than 1,200 inmates sentenced to less than a year.

The state's advancing rank in prison growth is due to the fact that Oregon was behind the curve in wising up to violent criminals and serious sex offenders. From 1960 through 1984, while violent crime rose by a factor of 7.2, the State of Oregon built one new prison with a capacity of 400 beds. Oregon has been playing catch-up ever since. As of 2001, Oregon was ranked 33rd among states in incarceration rate.

13. Although crime rates continued to fall in the 1990s, the state's overall population grew.

Crime rates did not "continue to fall in the 1990's". The violent crime rate in Oregon as reported by the FBI rose sharply from 1960 through 1979 and then stayed at that high level until 1996. Since then, it dropped six years in a row for a cumulative 41% decrease. Measure 11 took effect in April of 1995. We do not claim that Measure 11 is solely responsible for this decline but we do believe that it made a significant contribution.

While the article goes on ad nauseum about the fiscal impact of Measure 11, it completely overlooks the public safety impact. The decline in the violent crime rate from 1995 to 2001 translate to a total savings of 26,000 robberies, aggravated assaults, forcible rapes and non-negligent homicides. We believe that Measure 11 made a significant contribution to this savings.

14. A recent study by state officials, however, found that much of the increase in prison populations -- an estimated 64 percent -- could be attributed to Measure 11. Officials said that about two-thirds of this increase stemmed from the additional time inmates serve as a result of the mandatory minimums.

It should come as no surprise that, while Measure 11 was ramping up, it accounted for a major proportion of the growth in prison population. This is by design.

But the article should have mentioned another statistic from the DAS prison population forecast. Going forward, Measure 11 is projected to account for just 37 percent of growth (page 1 of the April, 2003 DAS prison population forecast).

15. Suzanne M. Porter, prison population forecast analyst for the Oregon Department of Economic Analysis, said she thought the remainder were an indirect result of Measure 11. Rather than go to trial and risk a long sentence, some Oregonians have pleaded guilty to lesser charges and agreed to serve several years in prison. Porter said these cases previously would have ended in probation or shorter sentences.

An unreported source of prison population growth is the phenomenon of judges using their discretion to order very long sentences for the most dangerous offenders, sentences that go far beyond what Measure 11 requires. The case of Ron Joseph Ayala, as reported in the May 30, 2003 Register-Guard, is an illustration. The judge sentenced Ayala to 29 years in prison for a vicious sexual assault on an 8-year-old girl. Measure 11 required a sentence of only 8 years and four months.

16. Health care is an even bigger expense, expected to run more than $80 million in the next biennium. One of the biggest costs is the aging of the prison population, which accelerated under Measure 11's longer sentences.

This gives the false impression that Measure 11 requires incarcerating people into their old age. Except for the 25-year sentence for Murder, the longest Measure 11 sentence is 10 years.

Furthermore, taxpayers would be paying the healthcare costs for many prisoners even if they were out of prison.

17. "Revenge," said acting Corrections Director Benjamin de Haan, "is expensive."

It is a sad day when the Director of the Oregon Department of Corrections can not distinguish public safety, personal responsibility and accountability from revenge.

18. The criminal justice system bore a share of the cuts, but the burden was not evenly spread . . .

The article portrays as irrational the completely reasonable idea that keeping the most dangerous criminals off the street is the highest priority of public safety. This makes perfect sense and is in alignment with the values of Oregonians.

19. "The more you put into that part of the social infrastructure of the state that means there's less money for schools and less money for health care," he [Governor Kulongoski] said.

On January 21, 2003, speaking at the kickoff of the Project Safe Neighborhoods program, Governor Kulongoski said:

"Ultimately, as important as education and all the other issues we talk about, if, in fact, the citizens of our state are afraid to travel the streets of their communities, or they are afraid for their own safety in their own homes, all of this isn't worth that much."

We couldn't agree more.

20. Without any changes to Measure 11 or other mandatory sentences, according to state projections, Oregon's prison population will grow 33 percent in the next decade to nearly 16,000.

Using the DAS estimate, if Measure 11 were changed so that its contribution to prison population growth were zero, then over the next decade we would have 14,520 people in prison and 1,480 additional violent criminals and serious sex offenders on the street.

Prison growth is not inevitable, even with Measure 11. The individual decisions of potential criminals determine the outcome. It is possible to live a felony-free life.

Article I, Section 15 of the Oregon Constitution sets out the principles on which criminal justice in Oregon is founded: public safety, personal responsibility, accountability for one's actions, and reformation. The only way to reduce the prison population without increasing victimization is to foster and promote a pervasive culture of personal responsibility.

Crime Victims United Responds To The Oregonian Article

More Background Information On Corrections

General Information On Measure 11

Does Measure 11 Deter Juveniles From Committing Crimes?